Palantir: Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

Palantir co-founder Joe Lonsdale has invested $11.8 million in Terra, a Nigerian technology company. It didn’t stop at money: Palantir board member Alex Moore has joined Terra’s board.

Founded by two Nigerians in their twenties, the company develops autonomous drones—and an accompanying “operating system”—to protect critical infrastructure across Africa: mines, power plants, dams. Foreign investment, especially when it reaches Africa, is usually good news. But when the investor is the “Palantir Ecosystem,” the color of the story changes. This is no longer a financial move; it is an argument about sovereignty. A partnership like this can shift the question of “data sovereignty” in Africa’s defense infrastructure toward one of Silicon Valley’s most controversial actors. Palantir has carried a dark reputation for so long that this possibility is already stirring serious anxiety in Pan-African circles—especially in debates about technological independence and the politics of security.

Terra’s young founders used to say: “Don’t buy Chinese or Western drones—they’ll surveil you. We’re local; Africa’s data will stay in Africa.” That line was more than a brand promise; it was a political claim. And that is precisely why the bridge now built to Palantir weakens the claim. Because the question isn’t only where data is stored. It’s also whose standards process it—and whose map of interests it is ultimately wired into.

The Far-Seeing Stone: Palantir

Palantir Technologies takes its name from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. The palantíri are crystal spheres that make communication with distant places possible. The Elves made these “seeing stones” to speak with friends far away; but when the Dark Lord Sauron seized one of them, everything was overturned. The stones stopped being instruments of communication and became instruments of surveillance and manipulation.

Enough Tolkien. Still, the metaphor neatly captures how the company positions itself: Palantir sells “seeing.” And in the modern world, seeing is the rehearsal of ruling.

Palantir Technologies: Yesterday

It began in 2003. Peter Thiel had sold PayPal for $1.5 billion and was now chasing a new idea: software that would “reduce terror” and “protect civil liberties.” In 2004, a prototype emerged. It was built by PayPal engineer Nathan Gettings and Stanford students Joe Lonsdale and Stephen Cohen. That same year, Thiel made his Stanford friend Alex Karp CEO. Palantir was founded by these five together.

At first they struggled to find investors. But in 2005, they crossed a critical threshold: $9 million arrived from In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s venture capital arm. That day, Palantir’s fate was tied to the American state. The CIA’s need was clear: it wanted to pull millions of scattered data points flowing from disparate sources into one place, connect them, and turn them into operational decisions. The technology Palantir built for the CIA was used in Iraq and Afghanistan for insurgent tracking and battlefield intelligence. It detected enemy positions and attacks—and likely saved American soldiers’ lives.

The CIA became the wind that filled Palantir’s sails, opening the road to the decision-making “operating system” it would build for the U.S. intelligence community: GOTHAM.

Today, GOTHAM is a global product, used predominantly by governments. But the project that turned Palantir into a global actor in the domain of war technology is MAVEN—and its story is striking:

In September 2017, the Pentagon launched Project Maven, an image-processing effort to identify targets from drone footage. The contract was quietly handed to Google; in 2018 it leaked to the press. A major “ethical crisis” erupted inside the company. More than 4,000 employees protested, saying, “We don’t build war technology.” Google was forced to withdraw. Peter Thiel called Google’s decision “treason.” In March 2019, the Pentagon transferred the software development work to Palantir.

From here on, the “tech company” story ends. Because what shapes Palantir isn’t only its technology but also its political and ideological orientation. Thiel and Karp’s position on the American right, their support for Donald Trump and J.D. Vance, and their closeness to Israel are matters of public record. They say destroying America’s enemies is a “moral imperative,” and that their technology exists for precisely that purpose. Palantir’s symbiosis with “state power” draws from this belief. That combination defines the company.

The Silicon Valley Philosopher: Alex Karp

I can’t not bring in Palantir CEO Alex Karp here. In many ways, Palantir is his reflection. Karp says he built Palantir to make the world safer—for himself, and for people like him. Is that still true? Debatable.

When Time included Karp in its 2025 list of the “100 Most Influential People,” it described his line like this:

“An unabashed techno-nationalist who openly preaches Western hegemony. The embodied form of the new generation of Silicon Valley billionaires.”

So here we have a billionaire who reads Nietzsche—and yet, at the end of the day, is beloved by the Pentagon.

A philosophy PhD with dyslexia. He says Palantir is “completely anti-woke,” thinks of himself as a neo-Marxist and a socialist—yet my reading is this: he loves grand declarations; his theories are often shallow, like a neon sign—dazzling, but lacking in nuance.

To me, the Huntington quote he included in a letter to investors captures Karp’s ideological posture:

“The rise of the West was not due to the superiority of its ideas or values or religion, but rather to its superiority in applying organized violence. Westerners often forget this fact; non-Westerners never do.”

It seems that from the Habermas he once admired, what remains in Karp is mostly a persona: the disheveled hair, the Tai Chi in the office. But let’s not treat this as a cute eccentricity. A man who once named fascism as his greatest fear may now be making its normalization possible.

And still, credit where it’s due: even if his answers collapse into a hard statist frame, he has at least started a conversation—opened a debate—about power, truth, and what a just society might mean.

Palantir Technologies: Today

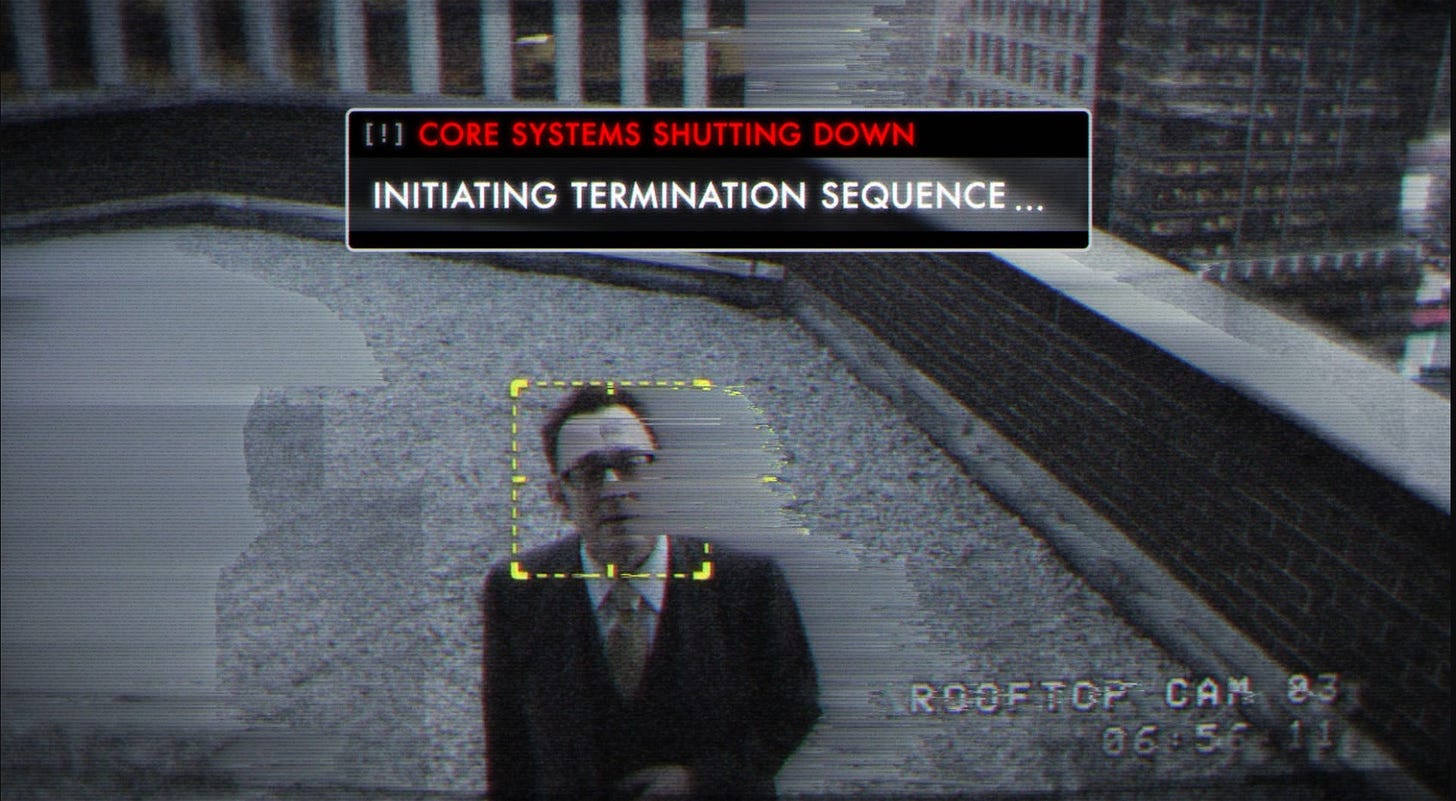

Today Palantir is firmly embedded in the U.S. military-industrial infrastructure. Its core customers include the heavyweights of America’s security bureaucracy—CIA, FBI, Department of Homeland Security, NSA, ICE—and business is growing fast. With Maven, Palantir used AI for battlefield awareness and opened Pandora’s Box. I think we will watch what spills out in the coming years on a global scale. Shuddering.

At this point, there is a rumor that shouldn’t be ignored: multiple sources have reported that “Lavender,” an AI project said to have been developed by the Israeli military to track low-level militants, was trained and used during the Gaza war on a database of Hamas members. Beyond that, there are claims that Palantir improved the system to extract patterns from intelligence data, generate probabilistic outputs through algorithms, and push target-prediction accuracy “to the heavens.”

I am choosing my words carefully here. Because Palantir has categorically denied these allegations—allegations that have sparked protests in many countries and provoked global backlash.

Tomorrow?

When a company like Terra says, “Africa’s data will stay in Africa,” what does it mean? The geography of the servers? Or the power to decide?

If this were only about money, the investment could be read as a success story. But security technology is not money. Security technology is alliance. It is standards. It is an invisible constitution that decides who counts as a threat, who gets flagged as “risk,” which lives are deemed “outside tolerance.”

That’s why the Terra–Palantir relationship may move Africa’s defense sovereignty beyond the level of “buying products from abroad” into something more complex: ecosystem dependency. What looks today like a board seat may become tomorrow a data architecture, a supply chain, a doctrine.

In this “Brave New World” where threats grow ever more asymmetric, is Palantir the last line of civilization’s defense? Would we be safer if our personal data—rather than circulating in the hands of gangs—sat with “large companies accountable to the state”?

You can treat all of this as the entrepreneurial success story of a group of tech-bros who read too much Tolkien. But when states reduce human beings to mere “data points,” they transform their relationship with the people they govern—and crack open the door to tyranny.

The final line of Person of Interest touches the heart of this essay too:

“If even a single person remembers you, then maybe you never really die.”

Let me add my own footnote to it: If even a single person is still aware that you are human, you have not yet been reduced to a data point. And perhaps the real struggle begins exactly here: staying human has now become a matter of security.

https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2025-peter-thiel-trump-administration-connections/

https://www.business-humanrights.org/de/latest-news/palantir-allegedly-enables-israels-ai-targeting-amid-israels-war-in-gaza-raising-concerns-over-war-crimes/

https://responsiblestatecraft.org/peter-thiel-israel-palantir/

https://theconversation.com/when-the-government-can-see-everything-how-one-company-palantir-is-mapping-the-nations-data-263178

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/25930212-the-scouring-of-the-shire/

https://www.theregister.com/2025/02/04/palantir_karp_comments/

https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2025/02/palantir-alex-karp-trump-private-prisons-profiteers/

https://www.ctpublic.org/2021-11-29/ex-google-workers-sue-company-saying-it-betrayed-dont-be-evil-motto